Search Results

48 results found with an empty search

- The Inquest into the death of Ronnie Nelson Began This Week....

CULTURAL WARNING: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander viewers are advised that the following post contains the names and stories of proud Aboriginal women now resting in the Dreaming. Veronica M Nelson: Inquest (vals.org.au) This is a really important case to firstly, ensure justice for Veronica and secondly, for many in the community. We at Harm Reduction Victoria are watching the inquest carefully to understand whether her health status impacted on how she was treated and why it appears basic duties of care were not followed in our Victorian system. This affects too many of us in similar situations. Aunty Donna Nelson, Mother of Veronica Nelson said: “This inquest is first and foremost about Veronica, and how a broken criminal justice system locked my daughter up and let her die while she begged for help, over and over.” As Percy Lovett, Veronica’s partner said: “Veronica was a strong woman – stronger than me. She’d always help someone on the street. She taught me everything about our ways. It’s got me beat how she knew what she knew. She knew everything.” “I don’t want it to happen again. I want to make it easier for the next women who get locked up. I want them to be looked after more. I want them to get more support and treatment in the community.” Moricia Vrymoet from The Victorian Aboriginal Legal Service (VALS) said, “It gives us some hope that the Inquest will examine the systemic issues surrounding bail laws and health care in Victorian prisons. We need the Victorian Government to pay attention and learn from their mistakes.” We are also sick of the harmful bail laws and outdated criminal codes being used against the community –particularly Aboriginal people. To everyone fighting on behalf of Veronica and our communities, thank you. Harm Reduction Victoria (photo of artwork by Nish Cash)

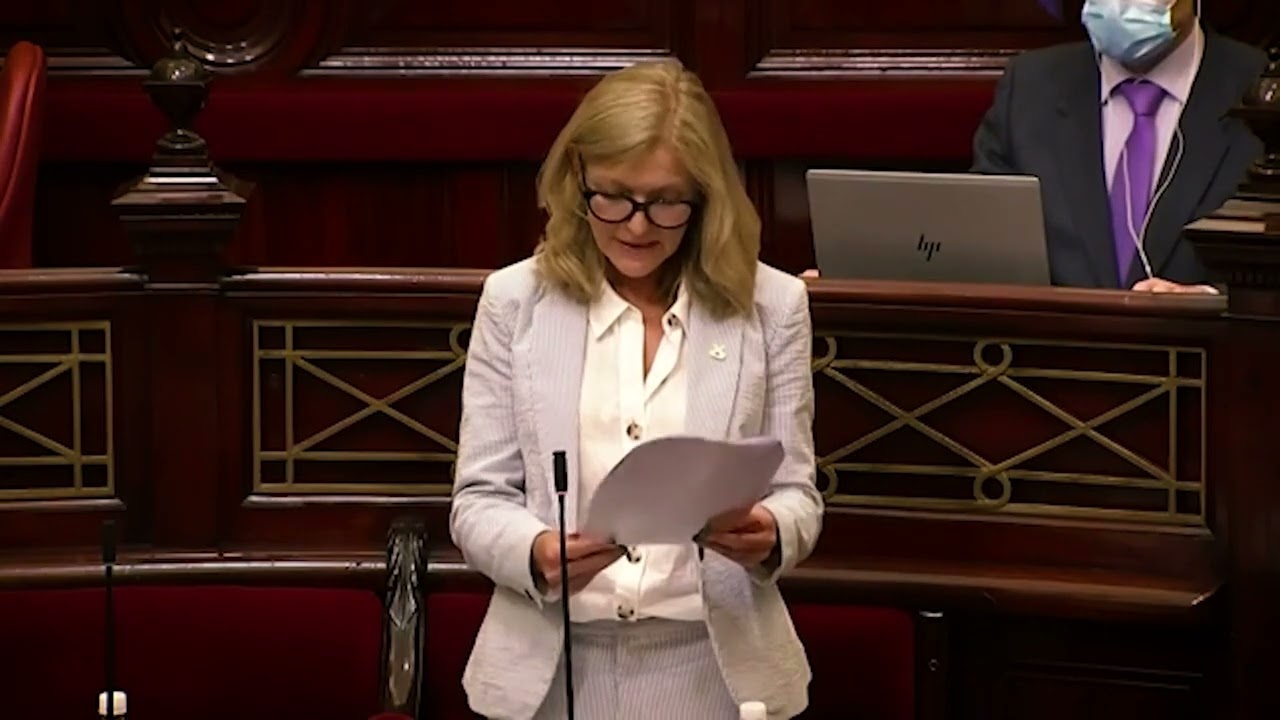

- Decriminalisation Bill introduced to parliament today by Fiona Patten

This morning, Fiona Patten introduced her bill to decriminalise the use & possession of drugs, into Parliament. We need #HealthNotHarm. .

- February 24 is Family Drug Support Day

Due to the impact of COVID-19 an event is being held online to mark the International Family Drug Support Day 2022. International FDS day first started in 2016 to draw attention to the importance of families affected by alcohol and/or drugs, including the benefits of supporting families. When families are given education, awareness and tips on coping and keeping safe, the outcome for everyone is improved. From small beginnings it has grown to international events in most Australian major cities and several overseas. The overall theme for the FDS events is Support the Family-Improve the Outcome. This year we are particularly focusing on 'Voices to be Heard'. FDS are focusing on the results of our 'Voices to be Heard' survey which collected information on the views of families around drug policy. The results will be presented to Federal and State governments on 24 February 2022. "Any family anywhere, regardless of background, economic and other circumstances can be affected by drugs. We hope this annual event will reach members of the community and change some of the negative attitudes that exist." Tony Trimingham, Founder and CEO of Family Drug Support. "The weight of the world was on my shoulders. We were so ashamed and alone - then we found support and things changed" Viola - Mother "What a difference it made being able to talk and have someone listen with empathy, and not tell me I was a bad parent or my approach was wrong. I can ring anytime and get stuff off my chest" Carlos - Father. The objectives for the International Day are; Continuing to push for productive changes in drug policy based on evidence and reducing harm Reducing stigma and discrimination for families and drug users Promoting Family Drug Support services for families and friends Promoting harm reduction strategies for families and friends Promoting the importance and benefits of supporting families The important role of FDS volunteers in providing family support across Australia Fatal and non-fatal overdoses from drugs including pharmaceuticals Promoting greater support and resources for treatment services

- Service Officer: Pharmacotherapy Advocacy Mediation and Support (PAMS)

Harm Reduction Victoria (HRVic) is seeking a non-judgemental person with excellent communication skills to join our Pharmacotherapy Advocacy Mediation and Support (PAMS) team. Please note, this is largely a client-facing role and the employment will be on a casual basis. The Pharmacotherapy Advocacy Mediation and Support (PAMS) service is a state-wide, telephone-based service that provides mediation, support, advocacy, referral, and information for those involved with treatment for opioid dependence (methadone and buprenorphine). HRVic is a community-based, membership-driven organisation, with a mission to advance the health and human rights of people who use illicit drugs and those on pharmacotherapy. We work to reduce stigma & discrimination against people who use drugs, and we strongly encourage people with a lived experience of illicit drug use – current, recent or past included – to apply. If you are interested in this role, please see the attached position description & instructions on how to submit your application or contact the email below if these are not linked APPLICATIONS WILL BE OPEN UNTIL FRIDAY, FEBRUARY 18, 2022 AT 5PM. For more information, please email admin@hrvic.org.au Position Description and Instructions for Applying below:

- WORLD HEPATITIS DAY 28.07.2021

World Hep Day 2021 videos- PATH- Peer Assisted Treatment for Hep C World Hepatitis Day is observed each year on 28 July to raise awareness of viral hepatitis, an inflammation of the liver that causes severe liver disease and hepatocellular cancer. This year’s theme is “Hepatitis Can’t Wait”. With a person dying every 30 seconds from a hepatitis related illness – even in the current COVID-19 crisis – we can’t wait to act on viral hepatitis. There are five main strains of the hepatitis virus – A, B, C, D and E. Together, hepatitis B and C are the most common which result in 1.1 million deaths and 3 million new infections per year. “Hep Can’t Wait and neither can social change." -Harm Reduction Victoria Statement on World Hepatitis Day 2021 For World Hepatitis Day 2021 Harm Reduction Victoria says that while Hep Can’t Wait, we also believe rapid, simplified testing & treatment can’t wait, more peer workers in hepatitis C treatment can’t wait, social equity can’t wait, and decriminalisation can’t wait. Harm Reduction Victoria fully stands behind the effort to eliminate hepatitis C in Victoria but believes that the social conditions faced by many people who use drugs are standing in the way of this drive. More options for simplified testing and treatment are needed so we can prioritise hepatitis C. Harm Reduction Victoria’s experience as the peer organisation for people who use drugs in Victoria gives us unique insight into the social dynamics and health needs of the community of people who inject drugs. Hep C, while a key issue for people who inject drugs, is unlikely to overtake the day-to-day priorities faced by the most marginalised of us. Due to criminalisation, stigma and discrimination, poverty, and the complications of managing dependence, many in our community already have an overwhelming burden of urgent issues to deal with. Immediate priorities like housing; employment; Centrelink or job service obligations; corrections requirements; child protection issues; raising money to buy food or drugs; all take up time and energy in daily life for many of us. While the community recognises that hep C treatment is beneficial for individuals, and elimination would be momentous; a disease that might cause death or illness in one’s future is almost never going to feel as urgent as the survival issues faced by PWID on a daily basis. If we are going to eliminate hep C by 2030, we will need to both assist people to resolve these issues and urgently attend to the structural issues that underpin our marginalisation – criminalisation, discrimination and social inequity. Right now, we need to ensure that those who wish to have a range of ways to access testing & treatment for hep C, including simplified one-stop testing and treatment, and we need to continue to find ways to make hep C treatment top of mind, including by incentivising treatment.

- Alcohol and other Drugs: Lived and Living Experience Advisory Group

Expression of Interest (EOI) The Victorian Department of Health recognises that the long-term strategic direction for Victoria’s AOD system must embed the expertise, views and preferences of people with lived and living experience of substance use or dependence and their allies & family members. To this end, the AOD Lived and Living Experience Advisory Group (LLEAG) has been established to support meaningful participation and partnership with people with lived and living experience of substance use or dependence, family members and supporters across a range of initiatives. The LLEAG has been meeting since September 2020 and currently meets bi-monthly within usual business hours. The Victorian Government is committed to ensuring that government boards and committees reflect the rich diversity of the Victorian community. We encourage applications from people of all ages, Aboriginal people, people with disability, people from culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds and from lesbian, gay, bisexual, trans, gender diverse, intersex and queer people. Expressions of interest are now open for additional members that reflect the diverse lived and living experience voices of the community. Active engagement of Victoria’s diverse communities is important to better understand and respond to the unique and specific needs of different groups and drive inclusive and equitable outcomes. Interested persons are asked to complete the EOI questions and return this form to: Edward Stott, LLEAG Secretariat, AOD Policy at edward.stott@health.vic.gov.au More information in forms. Download forms HERE > Please contact Edward Stott on 03 9595 2164 or via email if you have any additional questions, need additional support in completing the form or would like it in a different format. You can also reach out to us at HRVic HERE if you have any queries.

- About Time- No longer a crime to give out clean needles & syringes to each other

Good news! Finally the law has caught up with us taking care of each other. Today-Aug 4th 2021, legal changes in Victoria mean it is no longer a crime for community members to give out clean needles and syringes to eachother! Though many of us have been doing this for years and NSPs ask us how many people we’re picking up for, it has technically been illegal to give syringes to anyone other than yourself- until now! Alongside this development, naloxone distribution laws and regulations are also changing. How this will work is still being developed, but by the end of the year it should be possible for community members to walk into a service like an NSP and get take-home naloxone instead of needing a prescription or chemist to sell it. Both of these changes were recommendations from Victoria’s 2018 Parliamentary Inquiry into Drug Law Reform and HRVic has been advocating for these changes for years.

- The Trouble with Veins: A Conversation with Marguerite

It’s true. Bad veins can turn people away from Hep C treatment. The Hepalogue has touched on this issue a number of times, most notably in this earlier post. Users, whose veins have sustained permanent damage after decades of clandestine drug use, may shy from clinics they believe will negatively judge them. And, currently, even if such a person does front for a blood exam, treatment may still not progress if health workers cannot draw blood and the required analyses cannot be performed. It is often suggested that the number of people concerned is minimal - but among experienced users (a group highly likely to harbour Hep C) the problem is not uncommon. Surgical-style options do exist but the prospect of such procedures - plus the potential difficulty in accessing them - can cause some to shy away. Recently, I became acquainted with Marguerite, a veteran user with something of a tale to tell on this neglected subject. What better, I thought, than to interview a real person with seriously scarred-up veins to hammer home the point - to draw attention to how such wounds, beyond any medical considerations, can also be a focal point for stigma and discrimination – literal stigmata that, like Hep C, can persist for the term of one’s natural life. We were suffering through the shrivelling last hours of a heatwave, sitting in sticky black vinyl chairs at a cheap laminate conference table. I’m not familiar with Marguerite's customary dress sense, but today, owing to the weather, she was stripped back to a tee-shirt. On each forearm, she wore an elasticised compression wrap: the kind you may have seen in the front windows of pharmacies, on fit-looking dummies kitted out entirely in these ‘athletic support’ garments. However, Marguerite was wearing hers for emotional rather than athletic support. ‘My bruises and bumps and whacks and what not… I think they look ugly and horrible, so I’d rather just use these,’ she said, indicating the ‘sportswear’. She is in her early Fifties and started injecting seriously around eighteen - during the late-seventies/early-eighties, when there was a high prevalence of Hep C among Melbourne injectors. I’m guessing you picked up the virus pretty quickly? ‘I did. I was diagnosed when it was still non-A, non-B. (TGP: It wasn’t until the late ‘80s that Hepatitis non A, non B officially became Hep C.) What led you to get tested? ‘I was itchy.’ Sorry? ‘I was really itchy. No rash or anything, I was just itchy. I bought pinetarsol, I bought baby lotion, anything to stop the itching. I was scratching myself stupid. Pinetarsol... I used to bathe in that stuff. For me it was fleas. ‘So, I went to the doctor. He said: you inject drugs and you’re itchy... you’ve got hepatitis.' (TGP: Itchiness (or pruritus) is a common symptom of hepatitis. It is thought to be caused by a build-up of toxins in the bloodstream.) ‘And the doctor was right,’ continued Marguerite. ‘The tests came back positive. Then he told me I was going to die.’ Right. But how did you stop the itching? ‘I went to a naturopath and she got me to bathe in porridge.’ But… ‘I didn’t fill the bath with porridge. Imagine how much porridge I would have needed! And how would I have gotten it down the plug hole? ‘I put it in a stocking and rubbed myself with it. After a few weeks I was fine.’ You were a regular injector at this stage? ‘Yeah.’ And alcohol? ‘Nah. Maybe when I was in high school, but nah. Adult drinking’s not my thing. Has the Hep C led to any liver-related problems, over the years? ‘Nothing that’s landed me in hospital, or even at the doctor’s. I got septicaemia one time, but that was related to injecting – nothing to do with my liver. To be honest, after the itching incident, my Hep C was never more than just words on paper.’ Just a little more background... Are you on methadone at present? ‘Nah.’ Ever? ‘Oh, yeah.’ When was this? For a moment or two, Marguerite shuffled numbers in her head. ‘The longest I’ve been on it consistently is maybe… eighteen months? These days, if work takes me overseas, I’ll tend to go on the program for convenience sake.' ‘What about bupe. Tried that?’ ‘Yeah. When it was still actually bupe.’ Presumably, Marguerite was referring to the fact that Suboxone (currently the preeminent buprenorphine product in Australia) also contains Naloxone (Narcan©): a drug used to revive people from opiate overdoses. Taken sublingually, as prescribed, the Naloxone in Suboxone® has virtually no effect but, if one attempts to inject the medication, it reduces any buprenorphine-related high. Our government favours Suboxone® because it addresses the problem of ‘diversion,’ but some users baulk at the idea of taking a strong medication with no technical therapeutic value - Marguerite presumably among them. Subutex©, which contains buprenorphine and nothing else, used to be in general use, but has been generally superseded by Suboxone®. ‘I was on bupe when I tried rapid detox,’ she continued. Really? You did that? ‘Three times, actually.’ Really? Because you were... going overseas? ‘No. And I had two naltrexone implants. I tried the tablets once too.’ For the record, naltrexone is an opiate antagonist: a drug which binds powerfully to opiate receptors and, in sufficient doses, will negate the effect of opiates. It may cause sudden, precipitated withdrawal and is used in rapid detox. This is a technique which became popular in the early years of this century, but which has somewhat fallen out of favour due to serious risks and the questionable practices of some doctors. Naltrexone implants slowly release the drug into the system over an extended period (generally a month) during which opiates will have little or no effect on the client. The pill form, taken each morning, will do the same. Sounds like you were seriously trying to stop using? ‘Yep. I pulled up. I didn’t touch opiates for eleven and a half months.’ Wow. ‘Pretty good, huh?’ she said. Very. When was the last time you got it into your head to stop? ‘Probably… 2010?’ Think you’ll ever try again? ‘Nup.’ She paused, considered for a moment. ‘Nup. Don’t think so.’ Back in the day, did you consider having treatment for your Hep C? ‘I used to have a job supporting people who were going through the old treatment – interferon, ribavirin, that stuff. No fucking way was I going to put myself through the things I saw. It was awful. They went through hell. I don’t know anyone on that treatment who was able to maintain a full-time job. Luckily, the Hep C wasn’t affecting me, so… why the fuck would I put myself through that sort of ordeal? No way! ‘But then the new stuff appeared on the horizon, the DAAs , and here we are…’ You had blood tests? Along the way? ‘Yeah. The numbers meant jack shit to me, but I’d have liver function tests every six months or so. The doctor kept saying – well they’re high. The numbers are quite high… but nothing ever came of it.’ Every six months. That’s pretty diligent. ‘I was a sex worker. I had to have tests. And since they were taking blood anyway, I’d ask them to throw in an LFT.’ And all this time you were busy fucking up your veins? ‘Oh yes. Fucking them right up. I was a groin injector for a long time, after my arms became unusable, and that was fine. In a medical setting, it tended to really help if they’d let me take my own blood.’ More clinics are allowing clients to take their own blood, but many still do not. As for ‘groin-injecting,’ this is the practice of accessing the femoral vein (the principal vein running down the thigh) high up where the leg meets the torso. It’s not exactly recommended, but here’s a guide if you happen to be going there. Was the groin-injecting related to the sex work? It being a bad look having tracks on your arms? ‘It’s a bad look having tracks anywhere - sex work or not.’ Of course… ‘That vein’s gone now too. In the groin.’ Where did you go to after that? ‘After my groin? To fucking hell and back.’ From the expression on her face, Marguerite was in no way joking. So, the new Hep C treatments arrived. The DAAs. No injections, no major side effects. But you couldn’t get access because you couldn’t provide a blood sample? ‘Not for want of trying. They just couldn’t get blood out of me. No one could. I got to the point where I just didn’t want anyone putting another hole in me.’ I wonder, do you ever find yourself getting embarrassed in that situation? In a clinic, say. Having such bad veins? ‘Fucking oath I do. And not just in clinics. ‘If anyone else is around when I’m having a shot, they’re like: “Oh, do you want me to have a go?” Fuck off! No! I don’t want you to have a go! “Oh, I’ll be able to do it! I’ll be able to do it!” And if they weren’t my arms, I’d be saying, “alright then, smart arse, do it!” And, of course, they can’t. Know what I mean?’ I do. ‘You just get so frustrated! I’m to the point where I don’t inject in front of anyone anymore. Just because I’m sick of people putting in their two bobs.’ But, as I understand it, you did eventually manage to access the new treatments – despite your vein problems. Ýep. I did.’ How? ‘Someone I know went onto treatment. Someone with the same genotype as me. ‘And you know how most people clear it within the first four weeks? But you’re supposed to keep taking the medication for up to twelve weeks, just to make sure?’ Yeah. ‘Well, when this particular person had their four-week test, it turned out they hadn’t quite cleared it. So, the doctor – to be safe not sorry - ordered them a second round of treatment. And my friend gave me some of that.’ ‘How much exactly?’ ‘Two months’ worth.’ Let’s hope it was enough. ‘Yeah, let’s hope.’ Whilst saying this, Marguerite seemed unusually stoic. Even a little brave, to me, looking through the eyes of someone who has actively battled Hep C for decades. I can scarcely imagine how it would feel - having taken the treatment for Hep C, yet not being able to supply the fluids necessary to learn if it worked. The frustration. The anxiety. But Marguerite is very different to me and, plainly, she never let her Hep C get on top of her the way I did. Isn't it tormenting you? Not knowing? ‘Actually, I’ve got an appointment next week,’ she said with a sudden smile. ‘At the safe injecting room.’ The MSIR (Medically Supervised Injecting Room) is located in North Richmond. It is Victoria’s first safe injecting space and opened its doors to clients in mid-2018. ‘Supposedly, there’s a guy there, an anaesthetist. He comes in once a week and people say he’s the bee's knees. The duck's nuts,’ she added. Marigold indicated a point in the region of her left armpit. ‘I believe there’s one here. Just here… ‘ With increased concentration, she probed the area under discussion. ‘I just… can’t quite find it….’ She paused in her efforts. ‘You know they’ve got that Venoscope thing there?’ There are a number of hand-held blood-taking aids currently on the market. One is the Venoscope, which uses ultraviolet light to highlight veins. Many swear by it, but my own (admittedly amateurish) efforts left me feeling, at best, ambivalent. Beneath the pale skin of my arms, the device revealed a disturbing panorama of what looked like interlocking, gently pulsing spider nests. ‘I’ve got it into my head,’ continued Marguerite, demonstrating as she spoke, ‘that if someone can hold the Venoscope on my arm, just so… while I’m having a shot… then I’ll see exactly what’s going on under the skin. You know? While I’m poking it in…? I nodded. ‘You know how… sometimes, you get it in, but you have to… tap tap tap? To get the vein?’ Yeah. Or pull it back if you’ve gone too far? ‘That’s right.’ If he’s successful, this gun blood-taker, you’ll use the blood to find out if your treatment worked?’ ‘Yeah. After I’ve had a shot, of course.’ By the way, I’m assuming this person who gave you the DAAs - they wound up clearing their Hep C? Marigold eyed me stonily. ‘Of course.’ * Before I let you know about Marguerite's experience at the MSIR, I want to briefly touch on something else. I’d heard that some years back Marigold had been the (anonymous) subject of a feature in The Age. So, what’s the story with your media experience? ‘Well, they rang, wanting to talk to someone who used drugs, specifically ice. Obviously, someone had dobbed me in for it.’ Why ice? ‘There was a hue and cry at the time. 2007. The usual hysterics…’ Upon reading the article, I saw what she meant. Interestingly, twelve years ago, the authorities were inclined to put a damper on the subject, stressing that most of what we bought as ice was just ordinary old speed (dexamphetamine) and that any real ice sold was almost always of a very low quality. Interesting, isn’t it, the changes a decade can make? So, obviously you use ice as well as gear? ‘Yeah.’ You smoke it? ‘Yeah, but I was injecting it back then. I had to stop because of my veins. I save them for heroin now. ‘Don’t get me wrong,’ she said. ‘Agreeing to help with this article wasn’t an easy decision. I know that users get fucking taken advantage of all the time in the media. I know of people being offered fifty bucks by reporters wanting to photograph them while they hit up. Next thing - their face is on the front page of the Herald Sun. ‘The worst thing you can do is use your real name. That’s rule number one. I was involved in this harm reduction video where peers talked about their lives as injecting users. I used my real name for that – now, it’s the first thing that comes up when you google me. ‘Personally, I think I should be out and proud about my drug use, but… the reality is that sometimes I don’t want it out there. But it is! Permanently. Thanks to Google.’ So, this article…? ‘They wanted to come to my house,’ explained Marigold, ‘and observe me in my natural habitat. There was a writer and a photographer. They wanted to see me before and after I had my drugs. I explained that taking ice was the first thing I did of a day, even before getting out of bed. It didn’t faze them. They came round early. Before work. I answered the door in my pyjamas, set them up in the loungeroom with some coffee, then went back to bed and shot up. ‘When I came back out, they reminded me again to tell them when I’d had my shot. I told them I’d had it already. They were surprised. I think they were expecting a Jekyll and Hyde situation. What happened then? ‘They followed me around for a day. Followed me to a garage sale. I remember them sitting in the back yard while I hung out my laundry.’ What were they like, these people from the Age? ‘Perfectly charming. A little disappointed when I told them I didn’t do crime… So they had an agenda? ‘Yeah, they did. But they were honest and upfront about it. ‘The only reason I agreed in the first place was because they said they wanted to let the public know that there were people out there who used ice who weren’t crazy lunatic stereotypes… That’s why I did it. And, to be fair, the actual story did portray functioning and not functioning ice users… it was the editorial that ripped me to shreds…’ She was right. The editorial wasn’t exactly flattering to Marguerite. The writer of the main article also tracked the activities of a more disorganised ice user – the kind one typically sees in the tabloid media. Sadly, while Marguerite's photos were anonymised (she had a friend go through them to check for anything that might give away her identity) the other user allowed their face and emaciated body to be shown in all their lurid glory. But the editorial focused on Marguerite. The writer did everything they could to break apart the story of her being an ice-user who functioned as an ordinary citizen. They pulled out their blades and underlined each of her misadventures that might have been blamed on drugs, claiming, it seemed that there could be no such thing as a high functioning ice-user. Well, so much for the press. * I caught up with Marigold a few weeks after the first interview. So, you’ve done it? You’ve been to the safe injecting room, seen the anaesthetist? ‘I have.’ id you tell him about your plan? About finding that hidden vein? ‘Yeah, I did…’ How did he react? ‘ Well, he sort of nodded his head and seemed to be thinking “silly girl, I’ll show her what's what.”’ I hope he took you seriously? ‘Oh, yeah. Awesome guy. No judgement. We had a big chat and he understood that I’d exhausted just about every vein in my body. I let him know I’d been a groin-injector, but that I’d stopped after it caused a deep vein thrombosis (blood clot). He suggested that we try the other side of the groin, the side I hadn’t used. How many tries did it take? ‘One. He just pointed at the spot. I jabbed it in and that was that.’ So, you did it yourself? Of course. Why 'of course'? Weren’t you there to get tested? ‘This was the safe injecting room. I was there to have a whack. They won’t do that for you.’ But... the Hep C? ‘Well, I have been carrying around a pathology slip for over a year and, since we’d found a vein, I asked if we could take blood for analysis. He said “sure” and so we did.’ And you did that yourself too? ‘I did.’ Got the results yet? ‘Yes.’ And? ‘All clear.’ Congratulations. Do you feel different? Do you feel better? ‘You know… not really.’ Who knows what it is? Some people notice an immediate impact when their Hep C departs, others not so much. One thing that can be said with absolute certainty: your liver is better off without the virus greedily preying on its hepatocytes year after year, decade after decade… ‘It’s just never been a big thing for me,' said Marguerite. 'I was in a meeting and happened to mention that I’d cleared the virus. And everyone started cheering. It was weird. I mentioned it to my boss at work and he was the same. He said it was a big deal. Asked me why I was carrying on like it wasn’t. I just told him it didn’t feel like a big deal to me. ‘But I must say I feel a bit naked without it. I’ve lived with it a long time. Maybe it became part of who I was… in my head.’ That’s not unusual. As strange as it sounds, some people can feel a kind of separation anxiety…. What were the results of your liver function test? ‘My ALT was 9.’ That’s amazing. ‘Is it? I wouldn’t know.’ So, how are you doing with your veins now? Still using them daily? ‘Yeah.’ How’s that going? ‘I usually have a couple of attempts, and if that doesn’t work… I go intramuscular.’ So... the struggle continues? ‘Look, I’m pretty sure I’ll be using drugs till the day I die, so… I guess it does.’ -The Golden Phaeton

- A Man & His (Assistance) Dog: The Testimony of Azrael - Part One

Infected Again? Do not delay. And don’t be embarrassed. Health workers understand and are only too eager to help. Here’s an interview with someone who’s on his third round of treatment. (Please be careful not to rely on facts and opinions mentioned in this conversation. Their accuracy cannot be verified.) I interviewed Azrael, my hairdresser, in the late Spring sunshine, not far from his housing commission flat in St Kilda. Accompanying him was the boundlessly energetic Blaze, a chestnut coloured muscle-ball of a dog, who was determined to leave his mark on the proceedings. Azrael expelled a thankful groan as he made himself comfortable on the grass with his back to a tree. He’s in his mid-fifties, thin as a rake with long, perfectly straightened bottle-blond hair, a pronounced gay drawl and a massive personality. “Anyone got a cigga?” he asked. I think you brought some with you. “Hey?” he queried, looking mystified. I’m pretty sure you brought some with you. 'Oh. Right. Mnnn…' From somewhere on his person, he produced a tailor-made with a broken back. ‘Ugh. Menthol.' Forget that. Look in your back pocket. Azrael drew a flattened pouch of tobacco from the back of his jeans and set about rolling himself a cigarette. Predictably, attention turned to the youthful Blaze, who at this point was fetching a frisbee. Is he the same breed as your last one? 'Not really. He’s a staffy crossed with… something,’ he said, gazing at the dog adoringly. ‘Olly was an American Staffy. This one’s more English.' What’s the official description? Emotional support animal? “They’re called “Assistance Dogs”.’ Since Olly, his last assistance dog, passed on, Azrael has trialled three replacements, including the current one. I’d be surprised if Blaze didn’t get the guernsey (or, technically, the fluoro jacket). ‘The first was this massive crossbreed…’ Azrael’s vision clouded. ‘He only wanted cuddles…’ But… not up to snuff? ‘No. No chance. He was huge. Great with toddlers, with people, anything that wasn’t another dog. Those… well, he just wanted to shake them by the neck until they were dead. ‘We had to get him rehoused pretty quick, because the council wanted to impound him…’ How did that go? ‘He ended up somewhere on the urban fringe with a team of meth-smokers…’ Oh no. ‘They found him in an abandoned car by the side of the road. He still had the chip with my details, so I was called up to rescue him… I wound up sending him to a farm way up in Tamworth.’ A farm? When I was a kid, my dog Pluto was sent to a farm. ‘No. No. Not that sort of farm. This was a real farm, I can assure you. I’ve seen the pictures…’ You’ve seen pictures? ‘It was a real farm.’ Okay, I conceded. ‘So, the next dog, Gus, he used to, well… lunge at babies. At their faces. He didn’t work out well.’ I noticed someone being accompanied by his support dog during the Mueller inquiry. In the US. ‘I took Olly into court with me. They decided I was better off without a custodial sentence. I mean,’ he laughed, ‘how were they going to accommodate the dog? ‘Olly went everywhere with me. He’s done Gay Pride and all that. I used to take him to all the hospitals. The psyche hospital. He loved visiting that.’ The liver clinic? ‘Of course. He used to come up with me all the time. So, they understood that when he died I kind of… lost it a bit. This is The Alfred? ‘Yes. I was doing this longitudinal Hep C study there… ‘ Oh? Which one? ‘Not sure what the title was.’ (There’ve been a number of such trials: TAP, MIX, SuperMIX which have followed Hep C clients/drug users over time. All have been initiatives of the Burnet Institute) ‘I did the trial for a new Hep C drug to begin with. Then I agreed to become part of this study.’ You’d be about my age, wouldn’t you? ‘Yeah. 57 this year, I think… ‘Dog! Come here! Not everybody loves you, mate! Not everybody loves you… You big sticky beak!’ From a distant corner of the park came a sudden high-pitched yelp from something with the general size and shape of a sausage-dog. Azrael shook his head dismissively. ‘Blaze didn’t touch him, but he thought he’d start bawling anyway.’ Okay then, when did you first find out that you had Hep C? ‘I was diagnosed in the nineties.' And what led you to getting tested? ‘They were testing for everything at that stage. When everyone was dying of AIDS. It was a ghastly time…’ If I may ask… How did you avoid it? ‘More good luck, than anything. And a generous serve of cross-dressing.’ Really now? ‘Well, a lot of the people I slept with were straight. Or touted themselves as such - on the night.’ I’m almost following your logic... ‘I just wasn’t into the scene. You know? Where everyone was… you know… swapping pajamas.’ Say again? ‘Swapping pajamas. It was all very incestuous at one point, you know… Some were almost determined to catch it off their partners. Just to know what it was about… to feel the same way somehow…’ To feel part of the community? ‘Yeah. Yeah. And now it’s even worse. The rate of infection’s astronomical. All this bare-backing, you know…’ That would be… a decision not to use condoms? ‘Yeah. It’s all connected to ice…’ They’re calling that ‘chemsex.’ ‘No one has any other kind of sex now. Not on Grindr. It’s all chemsex, one way or another. The ugly ones, they’ve got the drugs. That’s how they get the prettier ones into bed.’ From time to time, friends and acquaintances dropped by the quiet park and lent their wisdom to the conversation. ‘And they let you know what they’re holding… like, ahead of time,’ said one girl about Grindr, ‘together with their preferences, like whether they’re tops or bottoms.’ ‘There’s always a transaction; a trade of some kind,’ said Azrael. ‘But somehow I’ve managed to avoid that too. ‘I’ve got a friend, he’s twenty years my junior. We’ve lived together on and off… I’ve watched him go through it all. ‘“Ice?” he says, “I never pay for ice. It comes with the deal. With whoever I get with that night. They all offer you free drugs to get you into bed.”’ Hep C is actually transmissible via heavy duty anal sex - if one partner has HIV. ‘Oh, okay. How’s that?’ asked Azrael. The level of enthusiasm maybe? The chance of blood on blood contact? ‘Your viral load would have an influence, wouldn’t it?’ mused Azrael. ‘Like, if you had a viral load of, say, 12, it would be pretty difficult to pass it on.’ Makes sense. But I don’t know the official line on that… What impresses me is that you’ve not only managed to avoid HIV, but you also seem to have been pretty proactive about your Hep C. How did you react when you first found out you had it? ‘Well… I’d been up a day or two. We used to take speed and go out dancing. A lot of people found commiseration on the dance floor in those days. And it was a dance floor that became less and less crowded, week by week it seemed, as people met their end… ‘But the actual day I learned about my Hep C… well I’d been out all night, dancing with Disco Down Tony Brown and a few others - and, yeah… I think I just started crying…’ Yeah? ‘I don’t know why. I didn’t feel sorry for myself or anything. I think it was more like… relief? That it was only Hep C. During that time, when the doctor called with something to tell you… well, your mind went to one thing and one thing only.’ Though Azrael was speaking of highly personal, intensely emotional things, I detected no hint of self-pity. His tone was even, and his voice did not quaver. If anything, he tended to smooth out the ragged edge of the subject matter with humour. How do you think you caught Hep C? ‘I was staying at a place in Punt Rd,’ he said, wistfully. ‘This one night, I was home alone, everyone else was still out… they hadn’t come home from The Peel or whatever was cool at the time. ‘I don’t know how you’d describe the mood I was in, but it ended in me discovering a loaded syringe taped to the underside of a desk. Of course, my first thought was… oooh! I wonder what’s in that!' And that’s where you got it? ‘Pretty sure.’ I think a lot of people – people who use - would do the same. I know I would have. At least, back in the day. ‘I squirted some out and tasted it to see what kind of analysis I could do with my tongue. It was definitely something.’ Speed or smack? I… can’t remember. Any good? No. Can’t remember. Whose was it? And were they angry? ‘Don’t know… I did listen at a few doors, trying to figure who might have put it away…’ Azrael drifted into a kind of nostalgic fugue. ‘But, yeah, around that period, there were quite a few queens who thought that sleep was for somebody else.’ His memories tripped from one to the next. ‘I don’t know… I think the speed from back then was a whole lot less damaging than this ice business…’ Oh, definitely. ‘And I did love my speed. I used to get dressed up as someone different every night. Sometimes, I’d spend more time getting ready than actually going out…' Did you sort your records? And your books? Did you rearrange the kitchen? ‘Disco Down Tony Brown would do everybody’s dishes for them.’ How long was it before you actually did anything about your Hep C? ‘Well, there wasn’t much to be done at first. I put it on the back burner. It didn’t seem to be affecting my liver, and I certainly didn’t want a biopsy to prove it…’ Biopsies. They can be nasty. ‘I never even had a liver function test - until the echo system came along. You know? FibroScan? ‘Yeah.’ How did that go? ‘My liver was fine. Not a scar in sight. Hang on…’ Azrael called out to a shabbily attired older gentleman who was shambling down a nearby path cradling a can of alcohol. ‘How are you?’ (inaudible) ‘Beautiful day. Heaven, isn’t it?’ (inaudible) ‘Enjoy your walk!’ Azrael’s attention returned to me. ‘He gets Bundy for this old man who can’t leave his house. He deals weed up there. And he got stood over by the same people who did me.’ In recent times, a particularly nasty thug had been giving Azrael grief. Azrael’s a friendly guy, trusting, sometimes too much so, and this dirtbag, once he’d ascertained the day on which Azrael received his pension cheque, would appear and roll him for money and drugs. Being the frail creature he is, there was little Azrael could do by way of defence. “But did I tell you?’ he announced excitedly. ‘I found him. In the newspaper. I’ve got it on my phone. I’m going to go to the cops this arvo and show them.’ Why was he in the newspaper? ‘He took the gun off a policeman and turned it on him.’ So maybe that’s over with now? Is he still a threat? ‘Well, he’s not at large anymore.’ That's a relief. Please click here for Part Two of this marvellous interview That’s a relief.

- A Man & His (Assistance) Dog: The Testimony of Azrael - Part Two

Continued from Part One) Anyway, back on track. When did you first get treated for your Hep C? ‘Well, I must admit, I did use my Hep C for everything I could. The pension. Accommodation was a big one. If I tried that now, it wouldn’t work ‘cause it’s no longer a death threat. But back then you could get housing off the back of it… all sorts of things…' And your first treatment? ‘That’s something of a tale…’ At this point, a guy appeared on a motorbike, reducing my recording to white noise. The only word I could make out of this segment was ‘Ducati’. ‘I was on those anti-smoking tablets,’ continued Azrael. ‘Not Zyban, the newer ones. ‘I called them happy pills. I loved them. I’d never been so upbeat. But I’d had the death of two parents as well, so I was a bit on the flat side too. And I was using heroin every day and my boyfriend didn’t have a clue. It didn’t interfere with our sex lives or anything. It was quite easy to keep it under wraps.’ Something happened with these pills? ‘That’s right. We were overseas. I don’t know if it was a combination of the pills and withdrawals, ‘cause over there I couldn’t score, you know… and it left me a little animated of an evening…’ Where were you? ‘We went to the Philippines.’ Safer back then. Today you could get shot. ‘I wound up getting some morphine. And nearly getting shot.’ Our interview was beginning to draw a small audience. By this point there were three or four people seated cross-legged on the grass in our near vicinity. ‘You know where Jess is?” asked someone. ‘Have you called him?’ replied Azrael. ‘I don’t have a phone. Could I borrow yours?’ ‘Lovely day for it,’ said someone else. ‘Hello Blaze!’ ‘Let me just phone Jessie.’ ‘Hi, I’m Raphael,’ said a man with ill-fitting false teeth. What happened overseas? I asked. ‘Well the boyfriend was having a whale of a time. He was twenty years my junior. An American boy with OCD. He started getting concerned that I wasn’t sleeping, that I was trusting the wrong people, that sort of thing, because I was quite elevated. I’d cool down a little at the end the day, but then I’d be up again. No sleep. Never any sleep.’ Trusting the wrong people is a bit of a theme for you. ‘You could be right,’ he mused. And then? ‘It didn’t get any better when we got home. So, yeah. He called the CAT team on me. And yeah, I ended up in the psych unit at the Alfred for almost a month.’ What was that like? ‘I could get out and smoke and everything. Didn’t make it to isolation. But I saw the rooms they use. They don’t have padded walls anymore. I think they found people are less inclined to throw themselves at walls if there’s no padding. ‘Anyway, on my way out, I wound up seeing this new doctor. Name was Jo King. Jo-king. Get it? She was the first doctor I’d had who did everything. And she was so capable. She was very good with my methadone and everything else I needed. ‘Blaze! Blaze Come on! Come here! Blaze! You are so naughty.’ Blaze lolloped towards us and made a surprisingly cat-like leap, over three wine glasses, avoiding them by millimetres. So, this Dr King… ‘She told me about these new drug trials that were popping up for Hep C. I’d heard a bit about them. That there were no side-effects, so she helped me get involved.’ So, you joined the study? Around 2015, I guess? That’s right. And it cured me. This was before DAAs were made generally available? 'Absolutely, yeah… And it came as quite a surprise for me that the government was going to pay that kind of money for junkies like us.' And you were using heroin… Everyday Same as now? Same as I’ve ever done. How long have you been on methadone this time? ‘I started not that long ago. Around when things began to get criminally violent. I put myself on a good strong dose too.’ What do you mean criminally violent? ‘I mean it got criminally violent. Debts that I took on. Rather than having them brutalise other people who were there at the time, who may or may not have taken the stash, I copped it for them.’ Sounds like a lot of stress. Anxiety. ‘Absolutely. It was nonstop. Then it all got entangled. Other dealers got involved and started fighting each other. Now they’re all in jail.’ So it was a help being on methadone? You mentioned a big dose? ‘I started on 80.’ That’s high. ‘I had to get something done quickly. I let them know I had access to it anyway, on the street, so no pussyfooting round, just whack me in the deep end.’ When you were on it previously. What era was that? ‘Oh Gosh. The nineties? For about six months.’ Was it a nightmare getting off? ‘For sure. I did it cold turkey. Off 35.’ That must have hurt. ‘I had to go down to Geelong for Christmas and didn’t want to have to worry about getting – or not getting – takeaways, and all the shit that goes with it… But yeah, it was bad. Some of the places your head goes when you’re in that situation… I had no support at all and I was living with a guy who was dying… I got back home to Prahran and went to bed. Then, when I woke up, these two thieves were taking the painting off the walls. They were ripping the place off. They mustn’t have realised I was in the bed, so when I woke up, they just started punching into me, the pair of them. I was like “I give up” and I turned over and went back to sleep. ‘When I woke up my stomach was, like, bloated with blood, because they’d done some internal damage. So, I called the ambos, they stretchered me out and I wound up with no memory beyond waking up the next morning… in the woman’s ward because they had no spare beds.’ Not because they thought you were a woman? ‘I don’t think so… I mean, they would have seen all of me.’ He traced a wide arc over his lower torso. ‘I had a zipper going from here to here. They’d had to get it all out and… you know, look at it. To decide what needed fixing. My spleen… they didn’t bother putting that back in.’ You lost your spleen? ‘Yeah, yeah. Another reason for not letting the Hep C get on top of me.’ At this point, Blaze lost patience with being well behaved. ‘Sit. Sit! Here you! Mista!’ ‘He’s a good find, mate. Good find,’ mumbled Raphael, whose voice appeared from time to time on my recording. Azrael continued his gruelling tale. ‘Then the guy I was living with died… of pneumonia, I think. One of the complications. I got discharged from hospital, arrived home to find that people had moved in. Don’t know how many, but they’d built a bonfire in the loungeroom, using doors and drawers and curtains and shelves….’ He shook his head in disbelief. ‘The place had perfectly good heating. Actual proper heating. But they preferred to smash up my furniture for fuel. The place was down on Beaconsfield Parade. Hollywood Mansions. You know it?’ I do. I had friends who lived there. ‘Beautiful Arts and Crafts building. Every fireplace was unique. Different one in each room. Lovely. The jewel in the crown of St Kilda’s Art Nouveau. It was heaven. Except for the occupants…’ After a discussion about St Kilda and its architecture, I pushed to get back on message, discussing Azrael’s history of injecting drug use. ‘I was eighteen, thereabouts, when I first came across heroin. Taylor and Eevie were the culprits. Hairdressers. And proprietors of St Kilda’s most dubious salon. Eevie used to deal to the likes of Brett Whiteley… ‘But in those days, mostly, my thing was speed. It wasn’t until I was older that I began to require… something to slow things down a little. Shortly after that, I discovered the virtues of heroin. ‘Also, and I scarcely need to say it, speed wasn’t uber-cool. Like heroin.’ Too true. ‘Nick Cave and those of his ilk were doing heroin. People aspired to be his dealer. Some regarded that as the pinnacle of success.’ Again, our conversation meandered. I steered it onto the subject of younger users and their Hep C experiences. ‘That “Tie me up. Hit me up” business has gotten big,’ suggested Azrael. ‘Or so I’ve been told…’ What? ‘Gay sex. Tie someone up, hit them up – with ice usually - then, I guess, you fuck them. There was something on SBS about it.' More chemsex? ‘Right on.’ You seem to hang out with a few of the young ones… Is there a good awareness level regarding Hep C? ‘Not really. No. Remember, a lot of them smoke their drugs, so blood-borne’s not a big issue. Sure, the lowly mongrel types will hit up anything they can get their hands on, but that’s always been the way.’ How did you first get reinfected? What’s the story? ‘I went and scored at The Gatwick.’ Someone you knew there? Or… just a guy in a room? ‘Guys in a room.’ Azrael shrugged. ‘They were extremely untrustworthy. Every one of them. The whole process… it was infuriating. And endless. I’m sure you can imagine. I’d been stuffed around so much, and then, to top it off, with the end finally in sight, I realised I had no fit. ‘No one had a fit. I asked around. No cleans. No dirties… ‘And then I found one. It wasn’t mine. Someone had left it in the bathroom. In the Gatwick. Jesus…. Obviously, I’m not proud of myself, but… I used it. I had a job that needed doing. Simple as that.' I hear you. ‘He was on a mission from god,’ added Raphael. How long before you knew you had the virus again? ‘I knew the minute I put it in my arm. ‘You know how sometimes, when you’re presented with a choice? And it’s no choice at all?’ I do. But I wonder, if, in the back of your mind, you were thinking: sure, I’ll probably get it, but I’ll just get rid of it again – was that your thinking? ‘I wasn’t too worried. I’d had it for twenty years and it hadn’t done me any harm. So, what if I get it again? Big deal. You know? As I said, my liver didn’t have a scar on it.’ You’re lucky. And you’re lucky the doctors are so gung-ho on retreating people. ‘For sure.’ So… you got yourself checked? ‘At some point I’d put my hand up for another two years of the trial, so I was getting checked regardless.’ And? ‘Well, I suggested to them that it might have come back naturally, when I knew it bloody hadn’t. And it turned out to be a different strain this time – so they knew what I’d been up to. I felt like such a dunce.' Different strain. Different pills? ‘It was a two tablets a day the second time.’ How long? ‘Same thing. Twelve weeks.’ When was this? ‘When Ollie was getting ill and dying. He came up with me to the Gatwick. So, he was okay then. I think he died after I finished that second treatment. Since then I’ve been trialling replacements.’ I reckon you might be lucky with this one. With Blaze. He needs to mature a little, that’s all… ‘Yeah. I think so too. He just has to pass the test.’ And so the conversation strayed back into dog-world. And thence, who knows how, into the dreadful story of how a girl tripped on an escalator and somehow got her lip caught in the mechanical teeth. She lost a tooth, but I felt she was lucky not to have her face stripped from her skull. ‘I have a horror of escalators,’ said Azrael, with a shudder. Do you notice the difference between having the virus and not having the virus? ‘Not really. It’s just something on a bit of paper that says you’ve got it - or you haven’t. But I’ve never had any sense of …’ Being sick…? ‘Yeah.’ So, we’re up to the third time, the third infection. I gather this fellow here was implicated somehow? I indicated Raphael, who was placidly nodding off a few feet away. Our audience had dispersed a little. Some were displaying obvious signs of impatience: not with our conversation but with a certain individual and his tardiness in the delivery of certain goods. ‘Yes,’ said Azrael, indicating Raphael. ‘There were three of us. We had a hitting circle. ‘We were all clear of Hep C because we’d all done the treatment… Raphael here, he was: I’m clear! I haven’t got it! And we were like – you’re in!’ Raphael exposed his blinding dentition and began to speak. ‘I gave you a choice, Azrael. I said, “you go first,” and you said, “no, mate, we’re clear, you go.” You were being gentlemanly, and I didn’t know I had it dormant. Just being honest here.’ How come you didn’t have your own fits? I asked. ‘It was payday,’ said Azrael. ‘There were plenty… or we thought we had plenty, but they’d all been used, so… so we thought, well, that’s alright … we may as well do it altogether…’ He cast a glance at Raphael. ‘Because we were a hitting circle and we knew we were all clear.’ Raphael chipped in. ‘I got it thirty years ago. They treated me with gamma globulin. I’m a courier. I can’t contract it, but I can infect people… it turns out.’ Now, you may be wondering. What’s all this about Raphael’s Hep C being ‘dormant’? And why was he treated with gamma globulin? It’s pretty clear that Raphael was getting his Bs and Cs mixed up. I’m no expert on Hep B, but I suspect that Raphael was referring to the immunoglobulins used (or perhaps once used) to treat the HBV virus. Also, people with Hep B cannot be permanently dormant carriers (or ‘couriers’) though at the time Raphael was treated this may have been the common wisdom. Raphael’s confusion is an example of how a poor understanding of BBVs can be a concern – to the point where a mixed-up soul may innocently spread Hep C in an otherwise well-informed community. So you gave it to Azrael? I asked Raphael. ‘Inadvertently, yeah. And it was only the one time…’ So, it was back to the Alfred for you? I asked Azrael. ‘Yes. Yes and No. I’m on the first month of treatment now.’ What drugs this time? ‘Epclusa.’ Well that should do the job I said. ‘You got the ciggies?’ said someone behind me ‘I would have been so embarrassed,’ continued Azrael, ‘had I not been in such a tailspin over the situation I’d got myself into financially - with these gangsters wanting to rearrange me for their thousand dollars. ‘I went to the crisis centre... saw Michelle… she’s a nurse that works in the infectious diseases part of the Alfred.' So the study didn’t test you the third time…? ‘I’d given up on the study. I was too embarrassed. I’d worked it out in my head that I was a failure. I was stupid to keep getting it again and again. It’s definitely a thing, you know, that feeling that you’ve let them down… they’ve done all this work for you and you’ve let them down by getting reinfected… ‘I felt like a right idiot. In the end I just got Dr King to write me the script.’ A vicious dog fight erupted out of nowhere and was quickly suppressed. ‘You got to watch out for those barky little ones,’ said Azrael. ‘Where did those rollies come from,’ said someone. ‘It’s alright Mr Smokey, no need to bark,’ said someone else. Azrael had moved onto the subject of parents - not so much his parents but the parents of gay children in general. ‘The same ones who used to turn their back on you and utterly reject you are all looking to include a gay in the family now, almost as a status symbol. Back then it was a blight. It was shocking. Now it’s something completely different.' Your parents still alive? ‘No. But I was adopted.’ Ever find your real ones? ‘I did. My mother was a corker. She was Jewish… ‘Sorry for interrupting,’ said Sandy, who had been loitering in the area for while now. ‘Youse want anything from Aldi?’ ‘The red,’ said Azrael, plumbing his jean pockets ‘The two-dollar eighty fiver…’ ‘I think they’ve run out of that,’ said Sandy. ‘Whatever you can manage, love,’ said Azrael. More talk. More wine. The subject of Hep C was forgotten. Now Azrael was talking about something I’d never heard of before. Polare. A secret language once used by the gay subculture (as well as sailors, wrestlers and fairground workers). ‘Baderthebonerone,’ he said. What does that mean? ‘Look at the gorgeous guy.’ I turned off the tape and, as I left, a car pulled up nearby. Among the half dozen or so gathered in the park, the sense of anticipation and impatience quickly dissipated. The Golden Phaeton.

- A Thousand Picks & Hammers: Eliminating Hep C by Sheer Determination

Some Last Words on the 11th Australasian Viral Hepatitis Conference I’ve mentioned that the big Hep C drug companies contributed significantly to the conference, both financially and with a considerable physical presence. Their pavilions were neon-suffused, architect-designed chill-out spaces stocked with sci-fi coffee machines and staffed by razor-suited reps with sharp, on-message responses to every query – and a certain snarkiness when it came to their big pharma neighbours. (Before I get too far, I should correct myself. In a previous post – one of the newsy ones – I mentioned that Merck & Co was ducking out of the Hep C market after the failure of one of their experimental drug combinations. Merck & Co is known as MSD (Merck Sharp & Dohme) in Australia and, contrary to my prior understanding, they remain in the Hep C game with their DAA (Direct Acting Antiviral) combo Zepatier, which has certain niche applications among patients with genotype four and/or kidney issues.) I asked the MSD people about Zepatier’s relevance in the age of big pangenotypics like Gilead Science's Epclusa and - particularly - AbbVie’snew blockbuster Mavyret. I was swiftly and eagerly appraised of Mavyret’s failings. These included an improbably long list of drugs with which it cannot be combined: several HIV meds, some statins, and Seroquel (all medicines which Hep C treatment candidates might conceivably be using). Later, I did a fact check. Some HIV meds, some antibiotics and St. John’s Wort are indeed contraindicated for use with Mavyret, but nothing else, or at least nothing I could find from an apparently trustworthy source. I don’t know exactly how hard these drug reps go at each other, whether they’d resort to slander, but maybe do a little fact checking of your own, in collaboration with your prescriber, whatever you’re prescribed. (And don’t, for heaven’s sake, read this as criticism of what, in Mavyret, may be the best Hep C combo thus far.) (Guest Speaker Dr. Sunil Solomon also happened to mention, in passing, a few adverse DAA interactions - mainly the HIV meds and by no means restricted to Mavyret - but more of Dr. Sunil soon.) During this research, I encountered something of a factoid which, for all my browsing on the subject of Hep C, I've never before noticed. It concerns Hep C patients who are co-infected with Hep B and the faint possibility that treatment with DAAs may reactivate that virus, even if dormant. I found packet warnings encouraging health care professionals to ‘screen patients for evidence of current or prior HBV infection before starting treatment.’ It turns out that such screenings have, since 2016, been a part of general practice in Australia. Because I was so quick out of the gate treatment-wise, I probably missed this, but don’t worry too much. In fact, don’t worry at all. The warning is less a warning than a covering of the arse and is based on tens of cases among tens of thousands. Absolutely, do not let it deter you from treatment. * There are 350 million people in the world with Hep C compared to 33 million with HIV. That's more than ten times as many people with Hep C than HIV - yet those with HIV enjoy the fruits of a planetary network of support and advocacy, while those with Hep C… well, not so much. The aforementioned Dr Sunil Solomon lamented this lack of funding and political will which is letting down the sufferers of Hep C. He asked if the extraordinary, community-fuelled efforts that germinated in the wake of AIDS had any equivalents in the Hep C world. If they might somehow be urged into existence. He dreamed aloud of what might result if HCV (Hepatitis C Virus) received the kind of attention enjoyed by HIV. But, as we know, these viruses differ in a way which locks in a yawning disparity when it comes to potential advocacy. And what way is that? It’s the stigma. The stigma that surrounds injecting drug use. The stigma so embedded in our societal norms that it is, as they say, enshrined in law. Dr Sunil Solomon is an Associate Professor of Medicine at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine. During the plenary session, he put on a compelling show. Beneath the rubric of ‘No One Left Behind,’ he concentrated on two mantras. The first was ‘every epidemic is different.’ Across the vastness of India, where most of his data was sourced, HCV prevalence varies from 4% to 64%, and in different sectors entirely different genotypes hold sway. When areas differ so fundamentally, it's obvious that tailored approaches are necessary. But that’s just India: the Hep C battlefront encompasses the world - and it’s not just the epidemiology which shifts. Cultures do too. And also governments. Consider Russia - home of Krokodil, and of a government so averse to harm reduction they even refuse to offer the basics (like ORT (Opioid Replacement Therapy: i.e. methadone) and NSPs (Needle & Syringe Programs) - then compare it to Australia where billions are spent on Hep C mitigation. Sunil’s second mantra? Integration. He holds, with cast-iron certainty, that the integration of Hep C testing and treatment with NSPs, ORT and other user-related services should be a ground rule that applies worldwide. His research was convincing. It demonstrated that if ORT is linked with Hep C treatment, it has the potential to produce extraordinary results. To some extent, Australia has adopted this same combinatory strategy, but as Melanie Walker of AIVL shows later in this post, we still have some way to travel. We are yet to fully exploit (and in some cases even identify) all points of contact between drug users and medical services. * According to Sunil, ‘every epidemic is different.’ However, the situation which prevails in India is very different indeed - at least to what we're used to in Australia. For a start, testing for the virus in India costs more than the actual course of treatment. In Australia, when last I looked, treatment was in the ballpark of $50,000. In India, I'm guessing, it would be one per cent of that. And as for hi-tech dosimeters? (At least one was presented at the conference, featuring, I think I recall, a foolproof laser grid) In India a cheaper method of ensuring treatment compliance is possible: that would be paying someone to go and actually put the pill in the patient’s mouth. There are also some unusual cultural factors in play. India is a land where receiving an injection from a doctor or nurse is deeply symbolic of healing. Sunil described a Hep C trial in which almost every participant who was randomised not to receive interferon (and therefore no injections) was deeply disappointed. They were sceptical that pills, ordinary everyday pills might ever be more efficacious than injections. To quote Sunil: We have such a high burden of Hep C in the general population because of our love for injections. It’s true! We want an injection for everything! We have a headache, we want an injection. We have a stomach ache, we want an injection… Even the flu-like fever caused by interferon is commonly seen as a positive thing, a sign that the injections are working. Speaking of interferon (pegylated interferon, to be precise) Sunil proposed that we ought not completely expunge it from our Hep C arsenal, despite the terrible reputation of its side-effects. In certain situations, he said, it may still be an optimal choice - particularly in combination with Ribavirin and certain DAAs, where it can reduce treatment duration to only four weeks. Ugh. Even typing the word ‘interferon’ makes me queasy. He used the devastating floods around Chennai in 2015 as an example. Pegylated interferon (with one injection per week) has a much longer half-life than DAAs (with at least one pill a day). During the floods, where many patients were separated from their medical providers and/or drug supplies, those on the longer acting drug experienced less of an interruption to their treatment. Sunil also made the point – an interesting one, I thought – that the miasma which hangs over the reputation of interferon may largely be due to the long-outmoded regimens of 24 to 48 weeks. If the drug had only ever been prescribed for four weeks, then the side-effects may have been more tolerable, and today it may not strike quite so much fear into the hearts of all those to who it has been prescribed. * Melanie Walker, the CEO of AIVL (the peak body for all Australia’s peer-based harm reduction outfits (including HRVic)) listed some areas of concern where the elimination effort is failing to penetrate - or experiencing less than spectacular success. Dealing with the virus in prisons is prominent in this regard, indeed the conference dedicated an entire track to this challenge. Melanie mentioned the obvious: the lack of any NSP services in prisons throughout the nation. This is a thorny issue, particularly with prison unions, but will ultimately need to be addressed. Hep C prevalence is very high in prisons – it’s the perfect place to get infected, or reinfected, but a good amount of thought and effort is being put into the treatment of prisoners. It’s just that the prison system is extremely clunky, systems are deeply embedded and difficult to work around, particularly in higher security prisons. A prisoner may have been successful in making an appointment with a Hep C treatment nurse; and on the day they may have gone through hours of processing needed to move from their unit to the clinic - when a sudden lockdown makes their effort fruitless, and another appointment must be made, for however long down the track. People are being treated in prisons, certainly, but the process is far from ideal. A prisoner may also be released midway through treatment. Keeping track of the comings and goings of prisoners is an unenviable task, and though work is being done in this area, maintenance of treatment after release is not yet systematic, although the Victorian state-wide prison treatment model run by St. Vincent's and funded by Justice Health is a good start. One frontier broached by Michelle was ‘chemsex’. This is a relatively recent term: it emerged from the HIV sector, but has been gaining relevance in Hep C, particularly with the proliferation of methamphetamine. Chemsex is defined as ‘sexual activity engaged in while under the influence of stimulant drugs such as methamphetamine or mephedrone, typically involving several participants.’ Obviously, behaviour like this can lead to disinhibition, and to risks being taken. Among those co-infected with HIV & HCV there is a chance that both diseases may be transmitted during unprotected anal sex. Safe needle-use practices may also be abandoned in such an environment. Of course, smoking is the traditional method of using ice, but Melanie pointed out that the seizure of ice-pipes by police, the inability of head-shops to display them for sale and NSPs to distribute them may be causing meth users to shift from pipe to needle - creating a risk of BBV (Blood-Borne Virus) infection. It’s absurd, really, that obtaining syringes should be easier and basically more legit than obtaining ice pipes. But this is not the only elementary harm reduction service that is hobbled by regulation. A licence is required in Victoria for the distribution of injecting equipment to anyone other than oneself. This has implications, for example, in rural areas unserviced by NSPs. Someone who travels to a larger town and brings home a box of clean fits to distribute among their friends is effectively committing a crime. Melanie stressed a need for legislation be quickly passed to iron out such anomalies, which seem to stand in the way of the state government’s stated Hep C elimination policy. * AIVL is also engaged in an investigation of users and aged care settings. ‘A greenfields site,’ as Melanie termed it, as it seems to be a subject which no one has properly addressed. What are people who have injected drugs for the bulk of their lives to expect if fate demands that that they retire to an old folks’ home? Nothing good, it seems. There is some evidence that users are actively avoiding engagement with aged care services precisely because they have no idea what they are stepping into. Are OST services provided? NSPs? Are there staff members with AOD experience? Will they be able to continue using their drugs of choice? To me, old age should be a time in life where such concerns should be put aside, not a time of anxiety-provoking change. But ugly images tend to come to mind if one pictures, say, the reaction of a commercial nursing home manager upon being informed that heroin is being injected on his premises. Horror stories regarding abuse of the elderly emerge regularly in the press - be it bedsores or kerosene baths. I shudder to think of how users might be treated, given the extra layer of stigma and discrimination to which they are reliably subject. Hep C infection, detection and treatment is relevant here too. Is there testing? Could there be testing? Perhaps on arrival? Is there an opportunity for treatment? The generation bearing the heaviest burden of Hep C in Australia will soon be facing their golden years. A progression into aged care or assisted living may be an opportunity to improve, or even save, the lives of those who, to that point, have slipped through the cracks. Who, perhaps, no longer have contact with services likely to offer HCV testing, or who may have avoided testing for reasons around stigma and discrimination. At the very least, one would expect relevant services to be offered, for staff to be familiar with the disease, to know how to address it, and to operate under sensible, informed policies. Perhaps this is already happening. Who knows? That's why it's such a good idea that AIVL had begun to probe the issue. * One talk which caught my interest (but for which I lost my notes) described the concept of trawling through Hep C notifications to check if the patient concerned had sought treatment, and, if not, to deliver a friendly suggestion. There was also discussion of how far back one could reliably go with this technique, given how personal details change over the years. To me such thinking is useful - if elimination is the goal. I understand that in Australia a relatively high percentage of Hep C cases have, at some stage, been identified. Why not proactively (and sensitively, of course) make use of that data? Finally, I’d like to echo the excitement around the rapid evolution of testing technologies. Simple dried blood spot essays for active virus should soon be a reality and processing time will continue to decrease. This opens the door for self-testing. Imagine being able to buy a Hep C test kit at a pharmacy -just like a pregnancy test or a bowel cancer screening kit. Just imagine that. * So that's it for the conference. I hope I've communicated the essence of it in these three posts, and in case you missed the first two, here they are No One Left Behind – Cunning Minds Bend the Generic into the Profound: A Reaction to the central theme of the 11th Australasian Viral Hepatitis Conference Head-Spins, Hangovers and Hair-Raising Instruments: Some Personal Reactions to The 11th Australasian Viral Hepatitis Conference The Golden Phaeton P.S. Beware the next Hepalogue post. I’ve got an absolute corker of an interview.

- No One Left Behind – Cunning Minds Bend the Generic into the Profound.